For decades, conservationists worried about losing wildlife and saving wild places. However, with more animals coming back and habitats restored after relentless efforts, they are grappling with a whole new set of challenges.

In Africa, the elephant population now stands at roughly 550,000, a genuine conservation win after decades of poaching pressure. In East Africa alone, numbers have climbed 15% over the past decade. But while the herds have expanded, their home turf hasn't. Kenya's human population grew nearly 60% between 2000 and 2020, and the ancient migration routes elephants once followed are now blocked by farms, fences, and towns that weren't there a generation ago.

The result is predictable as more elephants are packed into smaller areas, pushing into farmland, knocking down trees, coming into contact with people in ways that neither species particularly enjoys. In northern Kenya and Uganda, families living near parks wake up to find their crops trampled, sometimes an entire season's harvest gone in a single night.

The ancient migration routes elephants once followed are now blocked by farms, fences, and towns that weren't there a generation ago.

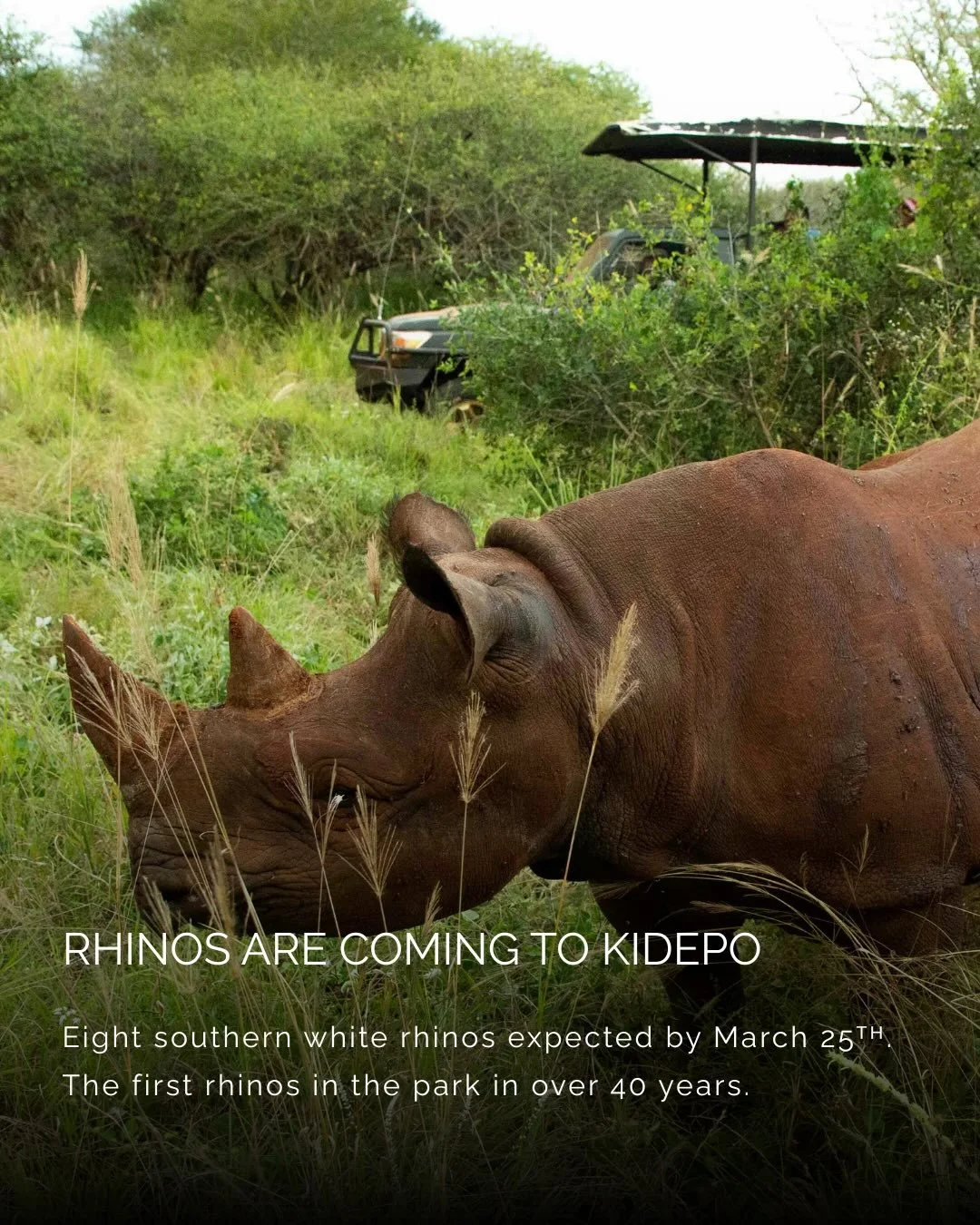

Kenya's black rhino story follows the same arc. The country's population plummeted from 20,000 in 1970 to just 381 by 1987 due to relentless poaching. Conservation efforts since then have been "almost too successful," as one Nature Conservancy report put it. By 2024, numbers had climbed back above 1,000, and Kenya now holds nearly 78% of the world's eastern black rhinos.

But many of those animals remain confined to small, heavily guarded sanctuaries built during the crisis years. For instance, the 92-square-kilometer Ngulia Sanctuary in Tsavo West was designed as a temporary refuge; for years it held more than double its ecological carrying capacity. Overcrowding led to territorial fights, injuries, reduced breeding, and higher calf mortality. KWS recorded over 300 rhino births in 2023 and 2024 alone, yet most of those calves died, a grim illustration of what happens when conservation succeeds faster than the habitat can accommodate.

The response has been the Kenya Rhino Range Expansion initiative, led by the Kenya Wildlife Service, which in December 2025 opened the world's largest rhino sanctuary. This expanded Tsavo West Rhino Sanctuary now spans 3,200 square kilometers (790,000 acres) and is home to a founding population of 200 black rhinos. The goal is to grow Kenya's population to 2,000 by 2037 and nearly 4,000 by 2050. In Laikipia, conservancies like Loisaba, which received its first rhinos in 50 years in early 2024, are creating connected corridors where animals can establish territories without killing each other for space. Four calves have already been born there, proof that the model works when rhinos have room to breathe.

In Montana's Blackfoot Valley, grizzly bears have been growing at roughly 3% annually since federal protections began in the 1970s

A Global Pattern

The tension between conservation success and its consequences extends well beyond Africa.

In Europe, wolf populations have surged 58% in just a decade, from around 12,000 animals in 2012 to over 21,500 by 2022. Germany, which hadn't seen wild wolf births in 150 years, now hosts more than 1,200. Every mainland EU country has wolves again. The ecological benefits are real—researchers found that wolves consuming deer and wild boar prevented between €2.4 and €7.8 million in road collision damages annually in France alone. But between 2018 and 2020, European countries recorded over 39,000 wolf-caused livestock incidents, costing €17 million in compensation.

In Montana's Blackfoot Valley, grizzly bears have been growing at roughly 3% annually since federal protections began in the 1970s, pushing back into historic ranges now dotted with cattle. Wolves followed in 2007. A fatal bear attack in 2001 near the town of Ovando brought tensions to a head. Ranchers who had coexisted uneasily with the occasional bear suddenly faced a permanent and growing population of predators on land their families had worked for generations.

Nowhere is the paradox sharper than in India, where Project Tiger has become both a triumph and a warning. When the program launched in 1973, the country's tiger population had collapsed to around 1,800 animals. Five decades later, India is home to roughly 3,700 tigers, nearly 75% of the world's wild population. The numbers keep climbing at about 6% annually and it is by any measure, one of the greatest conservation comebacks on Earth.

Tiger population growth in India has led to an increase in both human and livestock attacks.

However, it has also become deadly as human fatalities from tiger attacks crossed 100 in 2022, a sharp jump from previous years. Maharashtra's Chandrapur district, which is home to the famous Tadoba-Andhari Tiger Reserve, has become the epicentre of the crisis. The district held 30-40 tigers in 2006; today it has around 250. Between 2021 and mid-2025, 150 of the region's 173 wildlife-related deaths were caused by tigers. Schools have closed and curfews have been imposed. Families adjust their working hours to avoid dusk and dawn, when encounters are most likely.

With protected reserves filling up, the animals push outward into buffer zones, farmland, and villages. "High-density tigers and high-density people are a recipe for disaster," says Yadvendradev Jhala, one of India's leading tiger biologists. "We need to start thinking about this immediately." India has the space for more tigers, technically speaking. But 45% of current tiger habitat is shared with roughly 60 million people who collect firewood, graze livestock, and farm at forest edges.

What's notable across all these places—Europe, Montana, India—is that conflict levels don't track neatly with animal numbers. More than a third of European regions showed declining wolf conflict even as populations grew. Some Indian states manage large tiger populations with relatively few incidents. The difference isn't fewer predators. It's better management.

In Mugie Conservancy, a honey project on the edges of crop fields helps to both create revenue and put off elephants.

Learning to Share Space

The rewilding projects that are working have abandoned the old model of protecting animals inside parks while leaving people outside to fend for themselves. Instead, they put communities at the centre from the start, asking not just "how do we bring wildlife back?" but "how do we make sure people benefit when we do?"

In the Blackfoot Valley, that meant ranchers and wildlife officials sitting down together, something that would have seemed unthinkable a generation earlier. Through the Blackfoot Challenge, a coalition of landowners, state agencies, and conservation groups, they built what one retired U.S. Fish and Wildlife officer called "trust and credibility between agencies and landowners through civil meetings." What emerged wasn't a single solution but a patchwork of unglamorous fixes: electric fencing around calving areas, carcass pickup programs that keep dead livestock from becoming bear bait, range riders monitoring predator movements across 40,000 acres each summer. Annual human-grizzly conflicts dropped from 77 in 2003 to an average of 10-12 per year. Across 500 participating landowners, conflicts with wolves and grizzly bears fell by 90%.

In Kenya, beehive fences have proven surprisingly effective. Researchers from Save the Elephants and Oxford University tracked their use over nine years and found an 86% success rate at deterring elephants during peak crop seasons. Elephants genuinely fear bee stings on their sensitive eyes, mouths, and trunks. Over 14,000 hives have now been deployed across 97 sites in Africa and Asia, and farmers get honey as a bonus—one study period yielded a ton of honey worth $2,250. But even clever solutions have limits. During Kenya's 2017 drought, hive occupation dropped 75%, and effectiveness suffered for three years afterward. No single tool works everywhere, all the time.

Elephant collaring in Kidepo: the conservation focus is shifting from numbers to space-sharing, and technology is central to managing that transition.

That's why the most successful programs layer multiple approaches. GPS collars help rangers track herds and warn communities when elephants are heading their way. Strategic fencing guides animal movement while preserving corridors. In Tanzania's Manyara Ranch, community-led management cut human-wildlife conflict by 20% over five years. Save the Elephants has identified ten wildlife corridors in northern Kenya using 30 years of tracking data, with seven now demarcated and patrolled by local teams.

India is piloting similar approaches at scale. Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka have maintained relatively lower tiger conflict despite large populations, thanks to careful habitat management and prey restoration. The government doubled compensation for victims in 2023 and is testing early-warning systems using camera traps and mobile alerts. Conservationists are pushing for more wildlife corridors—strips of protected forest that allow tigers to move between reserves without crossing farmland. None of it will be enough if the underlying pressure isn't addressed but it's a start.

A 2024 study in PNAS found that conflict risk is set to increase by 2050, driven by climate change, cropland expansion, and population growth. But it also found that management practices matter more than predator numbers.

Supporting communities as we face this new set of challenges will be essential for ensuring gains are maintained and our planet continues to be home for a great diversity of creatures.

The Problems Worth Having

There's a strange privilege in grappling with too many elephants instead of too few, in worrying about grizzly encounters because the habitat has recovered enough for them to return, in watching tigers reclaim territories where they hadn't walked in decades. These are the problems of success, and they're infinitely better than the problems of failure.

But they're still problems, and pretending otherwise does a disservice to the communities living with the consequences and to the conservation movement that needs their trust. Rewilding is a constant negotiation between what nature wants to do and what human societies can accommodate. It requires flexibility, resources, and a willingness to keep adjusting..

The alternative, though, is a world without elephants pushing through the bush, without wolves howling in German forests, without tigers stalking through Indian sal forests, without rhinos establishing territories in Tsavo. That's something none of us want to live with.